Last week, Gal Beniamini, @laginimaineb published a series of blog posts discussing a chain of exploits that would allow an attacker to take total control of an Android phone by exploiting a Qualcomm Secure Execution Environment (QSEE) vulnerability. In this blog, we’ll discuss how many Android phones are affected by this critical vulnerability, according to our data, and what you can do to mitigate associated risks.

To be clear, though, this isn’t as dire as attacks such as Stagefright. Stagefright could be used to attack anyone remotely, and all you’d need is their cell phone number. This vulnerability requires that the attacker distribute the attack code via a malicious app. Google’s 2015 Android Security Report states that about 1 in 200 phones have Potentially Harmful Application(s) (PHA).

While Google’s security processes surely prevent many attempts to get malicious applications, it’s not perfect. If an attacker could bypass the screening process with a legitimate-looking application, they could social-engineer users into installing the malicious app. While the likelihood of getting malicious code onto a device is very low, all it takes is one “success” to get attack code in the Play Store.

Impact

This vulnerability (CVE-2015-6639) could be exploited on 60% of all Android phones seen by Duo, measuring from a data sample of 500,000 Android phones. For phones with the affected Qualcomm software, the only fix is the January 2016 monthly security update. Aside from Nexus phones, these monthly patches have to be applied by the manufacturer, sent to carriers, and then get approved and shipped by the carrier.

An analysis of Duo’s dataset of enterprise devices finds that 27% of Android phones are too old to receive the monthly updates, so they’re permanently vulnerable as well, unless (a) they update to Android 4.4.4 or later and (b) their manufacturer and carrier have built and approved a patch for that version of Android on that model.

While this doesn’t affect all phones running Android, it does affect the vast majority that have Qualcomm processors. According to Duo’s data, 80% of the Android phones that have our app are based on a Qualcomm chipset, usually in the well-known Snapdragon series (e.g., Samsung’s Galaxy S5 and S6, Motorola’s Droid Turbo, and Google’s Nexus line of phones). Of the Qualcomm-based phones seen by Duo, only 25% have applied the January 2016 (or later) monthly security update, leaving 60% of all Android phones vulnerable.

Before we discuss what the vulnerability actually does, though, let’s take a step back and cover some vocab related to the attack vector, the Widevine QSEE TrustZone application.

Background

TrustZone is used to create a trusted execution environment on mobile platforms. TrustZone refers to a collection of features included in ARM processors that allow two operating systems to operate simultaneously:

- A “normal” OS and

- A secure OS for sensitive operations, such as managing cryptographic keys and protecting hardware.

Qualcomm’s implementation of TrustZone, called “Qualcomm Secure Execution Environment” (QSEE), uses the metaphor of a “Normal World” and a “Secure World” to differentiate between the two.

The Normal World runs the Android operating system, while the Trusted World runs a barebones operating system that only manages these protected services and hardware. This establishes a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), an industry term to refer to setups like QSEE, which provide secure services.

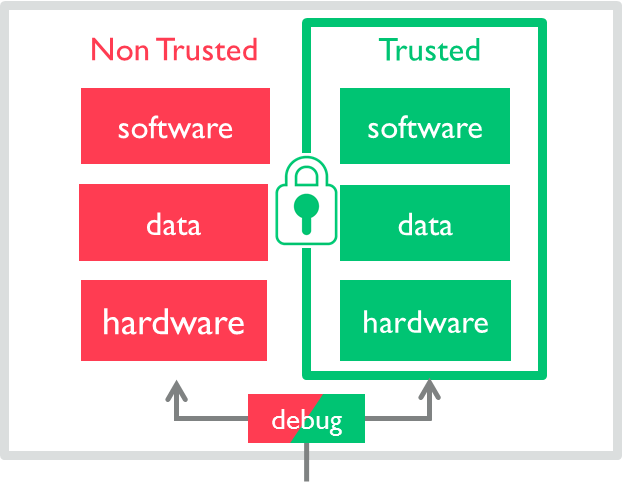

A Trusted Execution Environment separates trusted applications from non-trusted, so the trusted applications can perform sensitive operations securely. Note that the debug module would only be present during development. Source: Arm.com

A Trusted Execution Environment separates trusted applications from non-trusted, so the trusted applications can perform sensitive operations securely. Note that the debug module would only be present during development. Source: Arm.com

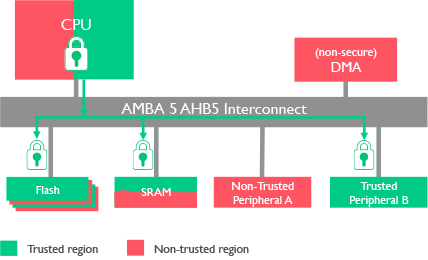

Qualcomm’s Secure Execution Environment uses the hardware support provided by AMD’s TrustZone to ensure that only secure memory and hardware (green) can only be read/written/used by secure applications (green) and vice versa. Source: Arm.com.

Qualcomm’s Secure Execution Environment uses the hardware support provided by AMD’s TrustZone to ensure that only secure memory and hardware (green) can only be read/written/used by secure applications (green) and vice versa. Source: Arm.com.

The Vulnerability

TL;DR

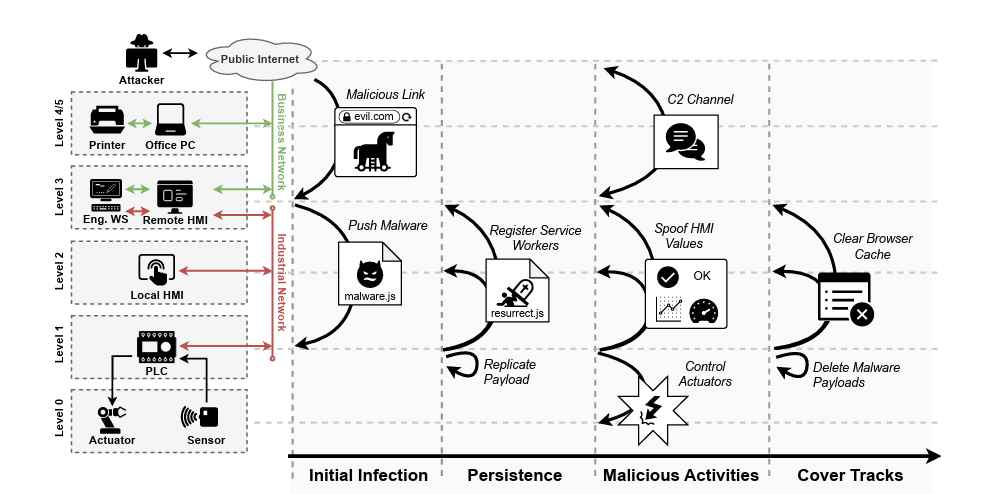

If an attacker can get a user to run a malicious app on an affected Android device, the attacker can gain complete control over the entire device by exploiting this QSEE vulnerability.

Slightly longer version: An attacker running code in the Normal World could take advantage of a vulnerability in mediaserver to exploit an application running in the Secure World. Then the attacker could modify the Normal World’s Linux kernel, allowing the attacker to compromise the whole operating system to whatever ends they’re trying to achieve.

Full explanation: Beniamini published a vulnerability they found that allowed them to gain the ability to execute arbitrary code in the QSEE. The ever-popular target, Android’s mediaserver had a vulnerability that allowed the attacker to take advantage of mediaserver’s special permissions to communicate with the QSEE. This attack requires exploiting some vulnerability in mediaserver, and we’re assuming that the attacker has one, given how frequently “Critical” or “High” severity bugs in mediaserver are found and patched (seven in May’s security bulletin, eleven in April’s, etc.).

Once the attacker can communicate with QSEE’s “trustlets” (trusted applications), if any of those have a vulnerability, the attacker can then exploit the trustlet’s level of access, which allows for accessing and modifying memory in the Normal World.

Beniamini found such a vulnerability in the “widevine” trustlet, which manages encryption keys for Widevine’s DRM software. They exploited that to “hijack” the Normal World’s Linux kernel; no kernel vulnerability required. Once an attacker has arbitrary access to the kernel, it’s game over; you can’t trust anything running in the Normal World.

This vulnerability is distinct from CVE-2016-2060, which recently made the news and also covered a vulnerability in QSEE. With some work, this too could likely be exploited to coerce Widevine (or some other vulnerable trustlet) to modify applications and data in the Normal World.

Another vulnerability in Widevine was reported as CVE-2015-6647, and it was patched at the same time as the one we talked about. It was generally ignored by the security community. The value of Beniamini’s work is found in chaining exploits together to completely pwn a phone, not just the more limited impact of any one vulnerability.

What Can I Do?

Here’s a few security recommendations for organizations:

- Check for updates to Android. Ideally, you’ll be able to update to the January 2016 security patch (or later). Unfortunately, many people that are running an updatable version of Android still can’t update, due to the long delay in getting manufacturers to apply patches, and getting carriers to send the patches to phones.

- Administrators can recommend that users use Nexus devices that receive more frequent and direct platform update support that doesn’t depend on carrier/OEM deployment to avoid associated delays.

- Make sure you only install apps from well-known companies. It’s not always easy, and definitely not fool-proof. But Facebook, for example, is a lot less likely to slip malicious code in its app, compared to lesser-known app developers that may try to make a quick buck by sneaking in malicious code.

- Using an endpoint visibilitysolution, administrators can also detect devices with missing supported security updates and encourage users to update. Or,warn and block users on outdated, vulnerable devices to keep them from accessing your company’s applications and data.

Using this level of device insight can help you create policies and take action based on data about your organization’s devices and users.

Source:https://duo.com

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.