“Common sense” is an oft-prescribed remedy for email-based malware threats: Don’t click on unknown links, don’t enable macros in documents from unknown senders, don’t even read emails from unknown senders. Threat actors, though, are testing the allgemeinbildung of German-speakers with personalized lures and social engineering to deliver ransomware and banking Trojans even in regions that have already experienced large-scale distribution of malware like Dridex.

Recently, Proofpoint researchers have observed numerous email campaigns targeting German-speaking regions, particularly Germany and Switzerland. Laden with banking Trojans and ransomware, these campaigns often require much more sophisticated protection than common sense.

By some estimates, global losses and costs associated with cybercrime annuallyreach into the trillions of dollars. Ransomware alone is expected to count for abillion dollars of this total in 2016 while banking Trojans, responsible for billions in losses over the last several years, continue to show new information and credential stealing capabilities. Losses go far beyond the direct costs of paying a ransom or dealing with fraudulent transactions, however. Earlier this year, for example, several hospitals in Germany were forced to reschedule operations and shut down a variety of connected equipment when they were hit with ransomware infections.

While the malware circulating in German-speaking regions in Europe is diverse, much of the impact on individuals and organizations can be traced to two major families: banking Trojans and ransomware.

Banking Trojans

Threat actors have historically had to choose between distributing malware at scale and personalizing attacks such as we see in spear phishing. Recently, though, we have observed larger scale personalized attacks that increase the effectiveness of email lures while still targeting larger groups of users. In German-speaking regions, banking Trojans like Dridex and Ursnif are accompanying these personalized campaigns.

However, it is worth noting that actors can easily swap out payloads, so the presence of one threat does not preclude the appearance of another in rapid fashion. Although not detailed here, Nymaim, for example, is another banking Trojan that we have observed being distributed in German-speaking regions. Similarly, whether or not the campaigns are personalized, banking Trojans have been responsible for considerable losses and, as described later, can still prove effective with more typical spamming approaches.

Personalized Dridex

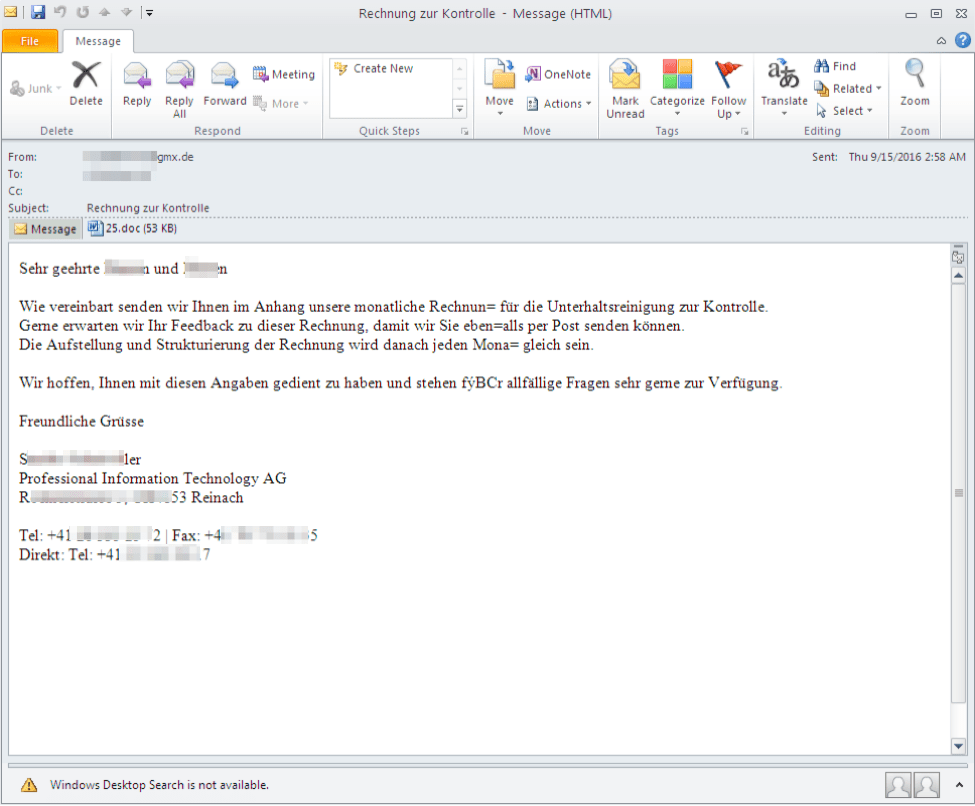

The Dridex banking Trojan continues to appear across regions, though at much lower volumes than we observed in 2015 and the first half of 2016. Instead, it is primarily being used in smaller targeted attacks and, in the case of the September campaign described below, contains injects for Swiss banking institutions. The lure, shown in Figure 1, is personalized in its greeting and references a “Bill to Control.”

Figure 1: Personalized Dridex lure

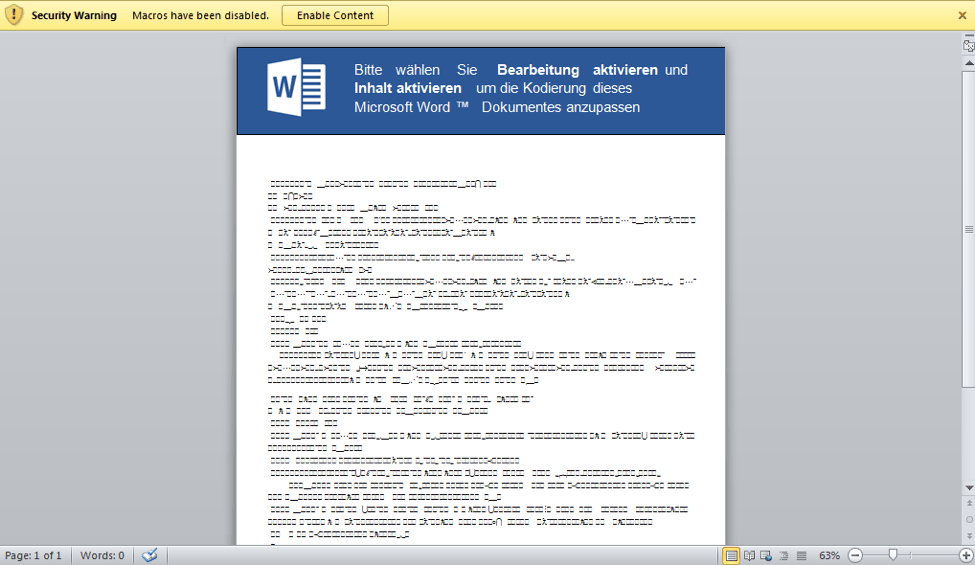

Figure 2: Malicious Microsoft Word document with macros that, when enabled, install Dridex botnet 144

This instance of Dridex is targeting primarily Swiss financial sites with the following injects:

^https://(wwwsec|inba|banking|netbanking)\..+\.ch/authen/login(\?|$)

^https://.+\.ch/(authen|WEB_XSA_LOGIN)/login\.xhtml

^https://ebanking\-ch\d*\.ubs\.com/workbench/

^https://cs\.directnet\.com/dn/c/cls/

^https://nab\.directnet\.com/dn/c/cls/

^https://www\.postfinance\.ch/ap/ba/fp/html/e\-finance/

^https://ebanking\.raiffeisen\.ch/entry/

www3\.bankline\.

pioneer\.co-operativebank\.

It is important to remember that the inclusion of a bank or service in the list of webinjects used by a banking Trojan does not indicate that the bank itself has been compromised. Instead it means that the customers of that bank are being actively targeted for fraudulent transfers and other theft by that malware.

The Dridex banking Trojan used in this campaign also targets the following applications:

crealogix,multiversa,abacus,ebics,agro-office,cashcomm,softcrew,coconet,macrogram,mammut,omikron,multicash,quatersoft,alphasys,wineur,epsitec,myaccessweb,bellin,financesuite,moneta,softcash,trinity,financesuite,abrantix,starmoney,sfirm,migrosbank,migros bank,online banking,star money,multibit,bitgo,bither,blockchain,copay,msigna,armory,electrum,coinbase,magnr,keepkey,coinsbank,coolwallet,bitoex,xapo,changetip,coinapult,blocktrail,breadwallet,luxstack,airbitz,schildbach,ledger nano,mycelium,trezor,coinomi,bitcore,avaloq,\*multiversa\*

This application targeting allows the Dridex operators to quickly and effectively profile a system for interesting software that could be targeted for financial gain. Other components provide keylogging functions for specific processes. These capabilities allow attackers to drop additional malware on an infected machine when they identify a client of interest.

Personalized Ursnif

Messages with a personalized email, which may include the company name in the body, subject, and/or attachment name, lead to the download of malware if the user enables macros in documents like the one pictured below. The “Personalized” actor distributing these macros has introduced an interesting new sandbox check, where the macro checks if there are at least 50 processes running on the victim system. Otherwise, the malicious payload is not executed. Moreover, the payload won’t be fetched unless the victim’s IP address is from Switzerland. These checks and others are detailed here.

Figure 3: Lure document with malicious macros enabled to download Ursnif

Retefe

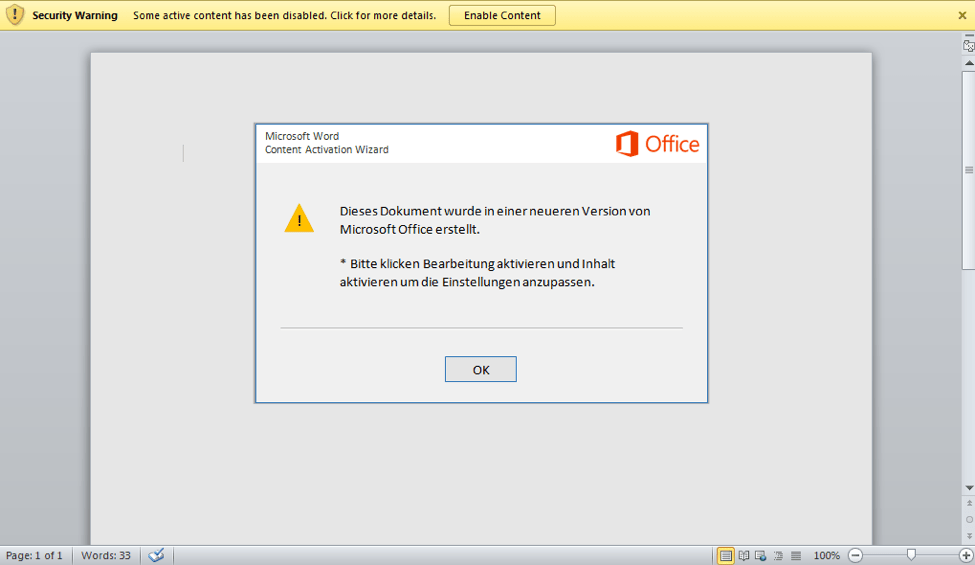

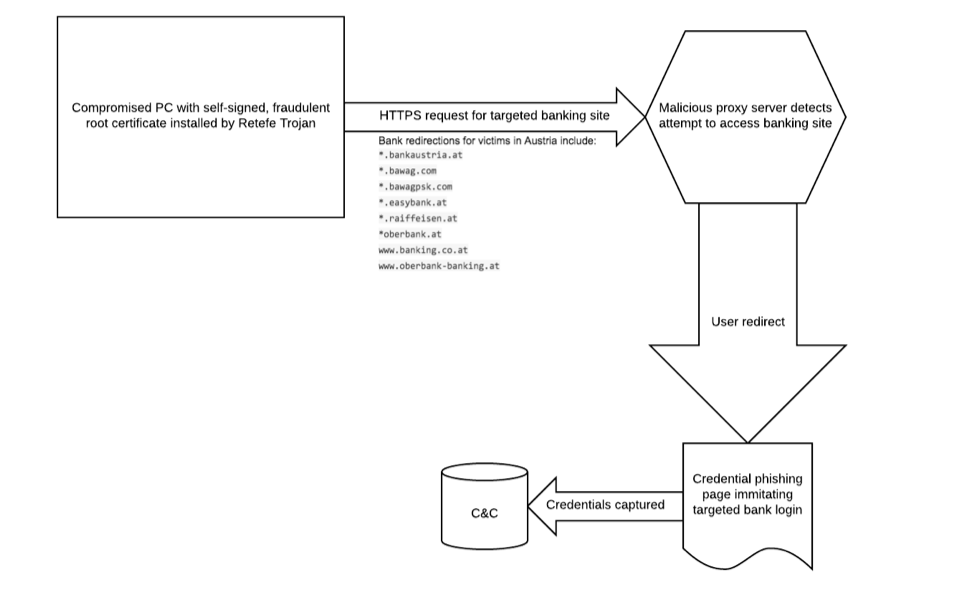

The Retefe banking Trojan has historically targeted Austria, Sweden, Switzerland and Japan, and we have also observed it targeting banking sites in the United Kingdom. Unlike Dridex, Retefe operates by routing traffic involving the targeted banks through its proxy (Figure 4). Retefe is delivered via zipped .js (JavaScript) files and, as in this particular campaign, via Microsoft Word documents.

Figure 4: Simplified traffic flow through Retefe proxy

Instead of the malicious macros we often observe, in this case the Microsoft Word documents used Packager Shell Objects to embed JavaScript into the document, as shown in Figure 5. The JavaScript (with the help of PowerShell) adds a certificate to the list of trusted certificates in Firefox and Windows. The script also sets a Proxy Auto-Config (Proxy-PAC) using a registry setting, such as the following:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\AutoConfigURL: “https://i3e5y4ml7ru76n5e[.]onion[.]to/7Zsdv5Eb.js?ip=<IP address>”

This request will return content based on the value of the “ip” query argument (the victim’s external IP address), making it possible for an attacker to differentiate the configuration depending on the targeted country or IP address range.

Note that this campaign is not personalized, opting instead for a more common shotgun approach.

Figure 5: Embedded OLE JavaScript object in a Microsoft Word document

Bank redirections for victims in Austria include:

*.bankaustria.at

*.bawag.com

*.bawagpsk.com

*.easybank.at

*.raiffeisen.at

*oberbank.at

www.banking.co.at

www.oberbank-banking.at

Bank redirections for victims in Switzerland:

*.bekb.ch

*.bkb.ch

*.cic.ch

*.clientis.ch

*.cs.ch

*.lukb.ch

*.onba.ch

*.postfinance.ch

*.raiffeisen.ch

*.shkb.com

*.suisse-ubs.com

*.ubs.com

*.ukb.ch

*.urkb.ch

*.zkb.ch

*abs.ch

*bcf.ch

*bcge.ch

*bcj.ch

*bcn.ch

*bcv.ch

*blkb.ch

*cash.ch

*directnet.ch

*eb.ch

*glkb.ch

*juliusbaer.raiffeisendirect.com

*nkb.ch

*postfinance.ch

*tb.bekb.ch

*valiant.ch

*wir.ch

*zuercherlandbank.ch

cic.ch

clientis.ch

cs.directnet.raiffeisendirect.com

e-banking.gkb.ch

eb.akb.ch

ebanking.raiffeisen.ch

netbanking.bcge.ch

tb.raiffeisendirect.ch

ukb.ch

urkb.ch

wwwsec.ebanking.zugerkb.ch

Other “bankers,” “loaders,” and “stealers”

In addition to banking Trojans, loader Trojans (or simply “loaders”) have evolved to include information-stealing capabilities. One such loader that we have observed in Germany and Switzerland is Pony, distributed via Rich Text Format (RTF) document lures with malicious macros.

Gootkit is also being distributed with German lures. A September 19 campaign used Google Docs URLs to link to zipped JavaScript files. When executed, these files downloaded an instance of the banking Trojan configured with web injects for a number of German and French banks as shown below:

https://banking.bank1saar.de*

https://*banking.berliner-bank.de/trxm*

https://banking.flessabank.de*

https://banking.gecapital.de*

https://banking.sparda.de*

https://*.bnpparibas.net*

https://*commerzbank.de*

https://*.de*abmelden*

https://*.de/portal/portal*

https://*.de/privatkunden/*

https://finanzportal.fiducia.de*

https://*kunde.comdirect.de*

https://*meine.deutsche-bank.de/trxm/db*

https://*meine.norisbank.de/trxm/noris*

https://*ptlweb/WebPortal*

https://www.comdirect.de/lp/wt/login*

https://www.targobank.de*

http*://*www.paypal.*

https://*abanquepro.bnpparibas/fr*

https://*credit-agricole.fr*

https://*lcl.fr/*

https://particuliers.secure.lcl.fr/outil/*

http*://*.paypal.*

Command and control domains included myfurer[.]org.

Again, these are yet more examples of the range of malware that threat actors are using in German-speaking regions to steal banking information and other credentials from users.

Ransomware

While banking Trojans appeared to be the malware of choice for many actors in 2015, ransomware has emerged as a dominant threat in 2016, both via email and exploit kits. Recently, Germany has been a target for one of the highest profile ransomware variants, as well as an unusual variant primarily limited to Central and Eastern Europe.

Petya Ransomware

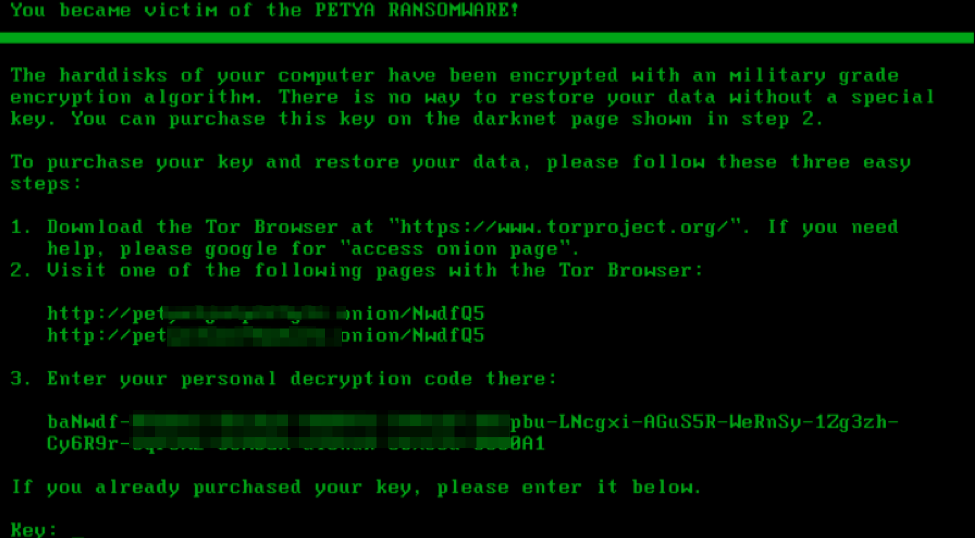

Although not as well-known as its more famous ransomware cousins such as Locky, Cerber, CryptXXX, and CryptoWall, the Petya ransomware family has recently emerged with a focus on targets in Central and Eastern Europe. In German-speaking regions, Petya ransomware was observed spreading via fake resumes, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: “Application portfolio” from [fake name] with picture

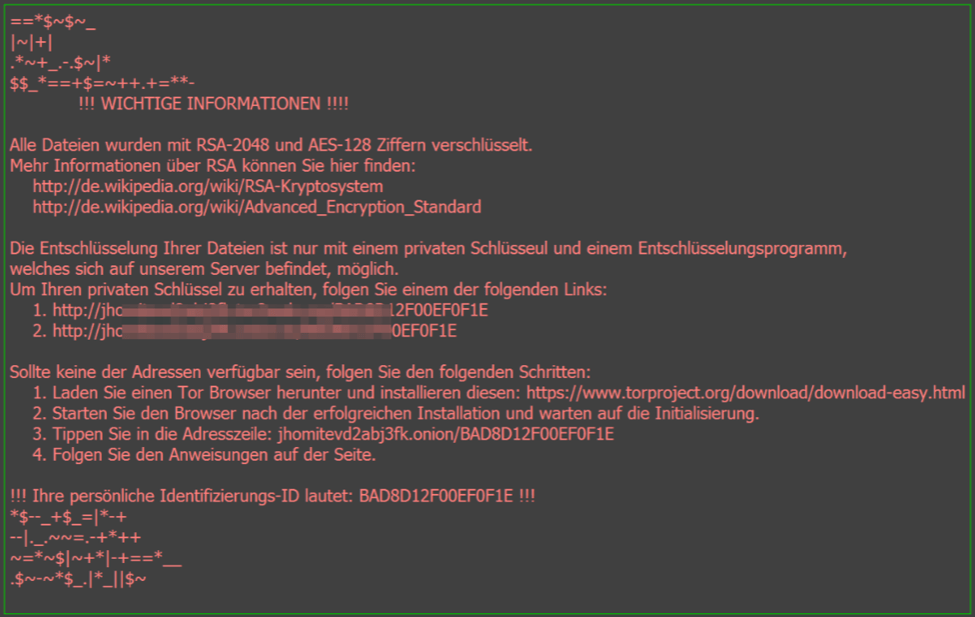

Petya ransomware does not encrypt files individually like many other ransomware variants currently in the wild. Instead, it uses a custom boot loader and very small kernel to encrypt the master file table on the disk. Petya’s dropper actually overwrites the master boot record with the custom kernel. Infected systems then reboot and users are presented with the screens in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7: Screen shown during encryption

Figure 8: Petya ransom message after encryption

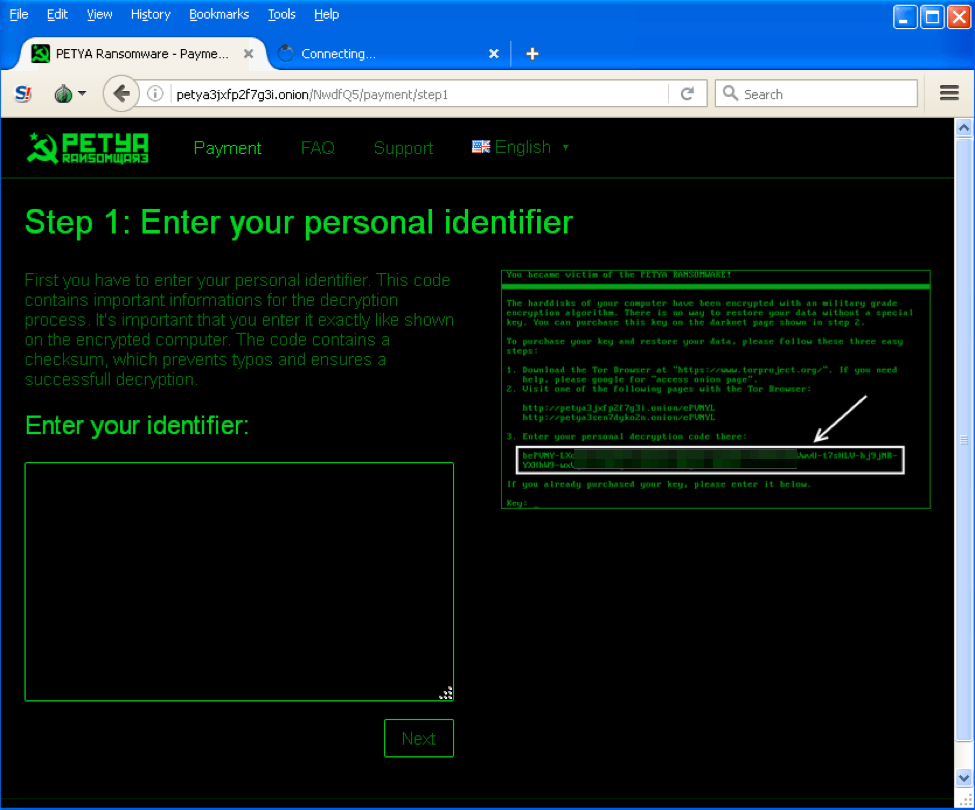

Figure 9: Petya payment portal

Locky

Driven primarily by the threat actors previously associated with Dridex, high-volume email campaigns distributing Locky ransomware have dominated the threat landscape since they first began in February 2016. In the third quarter of 2016, messages distributing Locky accounted for over 95% of global malicious email volume monitored by Proofpoint. German-speaking regions have not been exempt from these campaigns, as seen on on September 21, when we observed a campaign with both English and German lures leading to Locky Affiliate ID 3.

Messages in this email campaign purported to be from”

- “service@kids-party-world.de” with subject “Ihre Bestellung ist auf dem Weg zu Ihnen! OrderID 654321” and attachment “invoice_12345.zip” (both with random digits)

- “John.doe123@[random domain]” (random name, 1-3 digits) with subject “E-TICKET 54321” (random digits) and matching attachment “54321.zip”

- “John.doe123@[random domain]” (random name, 1-3 digits) with subject “Emailing: _12345_123456″ (random digits) and matching attachment ” _12345_123456.zip”

- “John.doe123@[random domain]” (random name, 1-3 digits) with subject “Receipt of payment” and attachment “(#1234567890) Receipt.zip” (random digits)

The attachments were .zip archives containing JavaScript (in .wsf or .hta files) which, if executed, downloaded Locky ransomware.

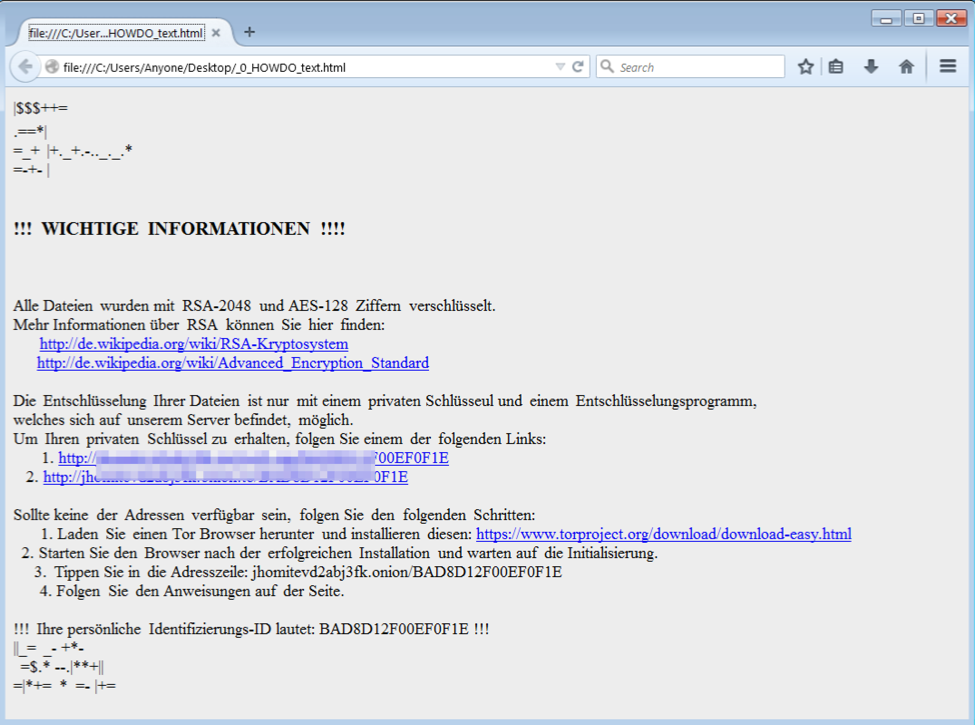

Figure 10: Newest version of Locky (.odin encrypted file extension) displaying a ransom screen in German language for a German victim

Figure 11: Newest version of Locky (.odin encrypted file extension) displaying a ransom screen in German language for a German victim

Conclusion

As much of Europe struggles with ongoing financial pressures, the relative prosperity of German-speaking regions may explain recent upticks in malware volume and variety, particularly in Germany and Switzerland. We have observed email campaigns with German messages and lure documents distributing multiple families of ransomware and banking Trojans in these regions, including variants like Petya that are uncommon elsewhere, as well as personalized campaigns for banking Trojans such as Ursnif and Dridex. We will continue to monitor this activity to determine if the increased interest in German-speaking regions is merely normal attacker variation or a sign of a broader trend.

Source:

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.