The story behind the Nefertiti Hack just got a lot stranger. But is it a hoax? Last month, two artists grabbed headlines across the world by announcing that they had snuck a hacked Kinect Sensor into the Neues Museum in Berlin and done a guerrilla 3D scan of the bust of Queen Nefertiti, a precious artwork from ancient Egypt. Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles called their work The Other Nefertiti and released their data file to world. Now anyone can have an incredibly high-quality reproduction of the sculpture, or remix it to make new artworks. But immediately, experts raised questions about the scan—it was just too high quality for a Kinect. Al-Badri and Nelles inflamed speculation when they refused to share more details about their scanning techniques.

The bust of Nefertiti has long been a bone of contention in the art world. Arguably, it belongs in Egypt, but German archaeologists took it from Amarna, Egypt over a century ago and have never given it back. Nefertiti holds a special place in ancient Egyptian history. In the 1350s BCE, her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten moved the royal palace from Thebes to the newly built city of Akhetaten (now Amarna). Together, Nefertiti and Akhenaten radically changed the structure of the state religion—some call it an early version of monotheism—and ushered in an era of unusually realistic art.

Al-Badri and Nelles displayed a 3D printed reproduction of Nefertiti’s bust in Cairo as part of their project, suggesting that only a high-tech heist allowed them bring this part of Egyptian history back to its rightful place. Their message, and the intriguing story of a covert museum scan, captured the public’s imagination.

Now it seems almost certain that Al-Badri and Nelles did not create the scan in the way they described. Artist Fred Kahl, who has made thousands of Kinect scans, argued that the Nefertiti hack scan was at a resolution that was far too high for a Kinect. There’s also the issue of Nefertiti’s headdress, which could only be scanned by holding the Kinect directly over the top of the sculpture. The artists shot video of their Kinect rig, hidden snugly under Al-Badri’s jacket and scarf, with no obvious way to hoist it above chest level. Writing for Hyperallergic, Claire Voon details many other experts’ problems with the scan, which contains roughly 2 million triangles. A typical Kinect scan contains about 500 thousand.

Cosmo Wenman, an artist who actually has done guerrilla 3D reproductions of classical art using high-quality digital photos, told Ars that he was immediately suspicious about the Nefertiti scan. Most likely, he said, the artists had been given a version of the Neues Museum’s own 3D scans, possibly by a museum worker or a third party who did the scans for the museum.

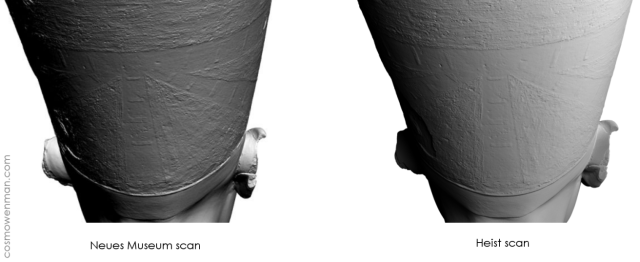

In a fascinating article, Wenman compares stills from the museum’s scan with the scan from The Other Nefertiti. He writes, “In my opinion, it’s highly unlikely that two independent scans of the bust would match so closely. It seems even less likely that a scan of a replica would be such a close match. I believe the model that the artists released was in fact derived from the Neues Museum’s own scan.” Representatives from TrigonArt, the company that scanned the bust for the Neues Museum, told Wenman that he couldn’t do his own analysis because “he is highly constrained with what he is allowed to do with the data.” This is typical for a company that does scans for museums, which closely guard their 3D reproductions.

Confronted with this evidence, the artists have remained coy. Al-Badri told Hyperallergic that she can’t “verify” the source of their scan because she got the Kinect from “hackers” whose identities she doesn’t want to reveal. These same hackers apparently extracted the data from her covert scanning, and they created the file for her and Nelles. She added:

Maybe it was a server hack, a copy scan, an inside job, the cleaner, a hoax. It can be all of this, it can be everything. We are not revealing details. We are standing by the fact that we actually scanned it, but we don’t want to dismiss the other options at the same time.

In other words, the source of the data file might have come from a more traditional kind of hack, where someone broke into the museum’s internal servers and grabbed it. Al-Badri even suggested they might have created the scan from a reproduction of the Nefertiti bust. The question is whether it makes any difference.

The web of half-truths and hints about how the scan was made could legitimately be part of the artwork itself. The point is that the data has been liberated, and now all of us have access to the data file. At the same time, there is something disingenuous about calling the data file “open” when it doesn’t contain truthful instructions on how other would-be scanners could do the same kind of project with other important artwork.

In addition, the true story of how the artists got their scan might actually be more revealing than the Kinect hoax. Wenman points out that many museums have high-quality scans of their artwork that they refuse to release to the public. He writes:

I know from first-hand experience that people want this data, and want to put it to use, and as I explained to LACMA in 2014, they will get it, one way or another. When museums refuse to provide it, the public is left in the dark and is open to having bogus or uncertain data foisted upon it.

Museums should not be repositories of secret knowledge, but unfortunately, as I’ve notedelsewhere, Neues is not alone in keeping their scan data to themselves. There are many influential museums, universities, and private collections that have extremely high quality 3D data of important works, but they are not sharing that data with the public.

He lists dozens of high-quality scans that are being hoarded by museums, from famous Rodin and Michelangelo sculptures, to Assyrian reliefs that are thousands of years old. If the artists behind The Other Nefertiti would come clean about where their scan came from, they might inspire other artists to force museums to open up their archives and allow many other artworks to return home—or come into our homes, making art part of our everyday lives.

Source:https://arstechnica.com/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.