A malware group is using Facebook’s CDN servers to store malicious files that it later uses to infect users with banking trojans.

Researchers spotted several campaigns using Facebook’s CDN servers in the last two weeks, and previously, the same group also used Dropbox and Google’s cloud storage services to store the same malicious payloads.

The previous attacks that used Google and Dropbox URLs were documented by Palo Alto’s Brad Duncan in a July write-up, and are almost identical to the ones detected last week by security researcher MalwareHunter.

The group uses Facebook’s CDN because the domain is trusted by most security solutions and there are low chances of having it blocked, compared to hosting malware on domains rarely active inside a business network.

Spam campaign hides malicious files on Facebook’s CDN

The infection process starts with users receiving a spoofed email from the attackers. These emails pose as official communications from local authorities and contain a link.

The links lead to Facebook’s CDN (Content Delivery Network). Attackers upload files in Facebook groups or other public sections, grab the file’s URL, and add it in spam emails. One of the malicious links might look like this:

https://cdn.fbsbx.com/v/t59.2708-21/20952350_119595195431306_4546532236425428992_n.rar/NF-DANFE_FICAL-N-5639000.rar?oh=9bb40a7aaf566c6d72fff781d027e11c&oe=59AABE4D&dl=1

RAR/ZIP files deliver Squiblydoo attack

Users who click on the link will download an RAR or ZIP file. These archives contain a link file (shortcut).

If users click on the link file, the shortcut path invokes a legitimate application installed on most windows PC — such as Command Prompt or PowerShell — to run an encoded PowerShell script. This technique of using local applications to hide malicious operations is known as “Squiblydoo,” and its purpose is to bypass lower-end security software.

From this point on, the encoded PowerShell script downloads and runs another PowerShell script that starts a storm of operations. The second PowerShell script downloads a loader DLL file, which in turn downloads a legitimate EXE file and a second DLL.

The twisted maze of operations continues with the creation of another link (shortcut) file that points to a VBS script. The PowerShell script then invokes the shortcut file, which in turn invokes the VBS script, which in turn executes the legitimate EXE file, which in turn side-loads the second DLL file.

Group is going after only Brazilian users

According to MalwareHunter, during these twisted procedures, the group also checks the user’s geographical location based on his IP address. If the victim is not from a target country, the infection operation will be aborted and the infection routine will download (and eventually load) an empty last-stage DLL file. But if the victim is from the target country — Brazil in this campaign — the legitimate EXE file side-loads a malicious DLL file.

This DLL file then downloads and install Banload, a malware downloader that is later used to deliver a banking trojan that targets Brazilian users only, which ESET detects as Win32/Spy.Banker.ADYV.

Win32/Spy.Banker.ADYV was seen in live infections earlier this year, in July 2017, by ESET’s Brazil division, in a campaign known as DownAndExec, also carried out by the same group.

Researchers believe this is the same malware group behind the Banload campaign that targeted Brazil in 2016, and another campaign that pushed the Escelar banking trojan in 2015, also targeting Brazilian users primarily.

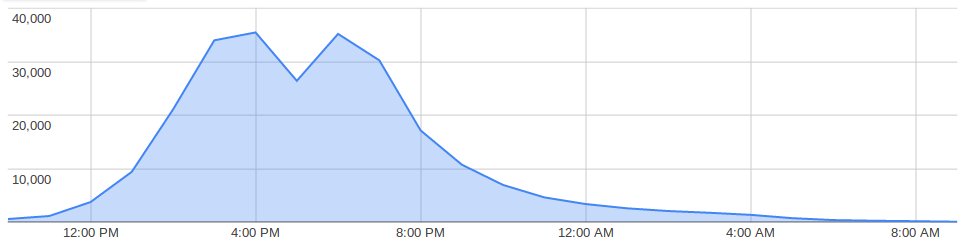

Hundreds of thousands received the spam emails

MalwareHunter, the researcher who spotted the recent activity from this threat actor, describes them as very sophisticated, even more so than some recent nation-state cyber-espionage groups.

The threat actor also possesses the firepower to carry out large spam campaigns that push out the malicious emails. The group borrowed techniques from online marketers and used 1px by 1px tracking images embedded in their spam emails to see who opened their emails. These small images were loaded via goo.gl short links, allowing MalwareHunter to detect the campaign’s reach. For example, a campaign MalwareHunter spotted on September 2 pushed out emails that were viewed by at least 200,000 Brazilian users. Two other campaigns also garnered between 70,000-80,000 views each.

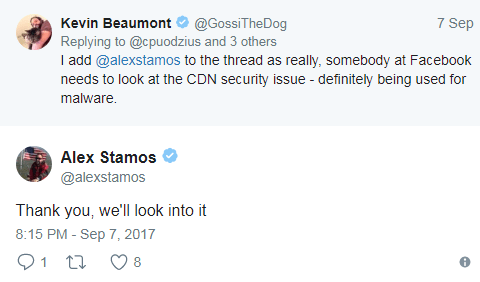

Currently, the campaign has subsided after raging strong for almost a week, but experts expect it to come back once more, with yet another small variation. Facebook was notified and is also looking into the issue.

IOCs:

RAR file: 1faa46ba708e3405e7053cde872c65cc7a7d7fbf6411374eb6e977f20c160e16

DLL file:41e463cd5d4cf20d02bb7cd23b70465480d1cd5cd3c9f8653e9f93b3a85124d8

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.