The Intellexa Leaks have transformed Predator from a partially understood “mercenary spyware product” into a clearly mapped, industrial-grade offensive surveillance platform. The leaked training videos, internal OPSEC documentation, marketing decks, and corporate records provide a rare inside view into how Intellexa designs, deploys, and operates Predator in partnership with government clients across multiple regions, even after successive waves of U.S. sanctions.

1. Investigation Overview and Operational Context

The Intellexa Leaks are the result of a joint investigation by:

- Inside Story (Greece)

- Haaretz (Israel)

- WAV Research Collective (Switzerland)

- With technical analysis by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, and corroborating threat research from Google Threat Intelligence / TAG and Recorded Future’s Insikt Group. Amnesty International Security Lab

The leaked corpus includes:

- Internal Intellexa documentation: architecture and OPSEC guidance.

- Sales and marketing material, including descriptions of the Aladdin “almost zero-click” infection system.

- Multiple training videos in which Intellexa staff remote into live customer environments and navigate Predator’s backend dashboards and logging systems.

These materials, combined with prior work (Predator Files, earlier TAG and Amnesty analyses, and Recorded Future infrastructure mapping), show Predator as:

- A multi-component platform with clearly delineated infection, C2, and analytics tiers.

- A vendor-visible system, where Intellexa staff retain live access to customer environments and logs.

- An ecosystem increasingly integrated with ad-tech infrastructure and opaque corporate shells in jurisdictions such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi free-trade zones.

Despite sanctions by the U.S. Commerce Department (Entity List, July 2023) and U.S. Treasury (Intellexa Consortium and related entities, March 2024 and extensions), Predator infrastructure remains active and continues to adapt.

2. Predator as a Platform: Architectural Model

The leaked training material and corresponding technical analysis expose Predator as a layered system designed for repeatable, multi-tenant deployment. Amnesty’s briefing and Recorded Future’s infrastructure mapping align on the following components.

2.1 Core Operational Components

The platform’s backbone is composed of:

- Infection Servers

- Dedicated hosts that deliver exploit chains and decoy content.

- Typically fronted by domains masquerading as news outlets or benign services.

- Implement device fingerprinting logic (e.g., user-agent parsing, JavaScript capability probing, IP/geo filters) to decide whether to serve an exploit or a harmless decoy.

- URL Shortener Layer

- Internal “short link” infrastructure (often represented in logs as

urlch1l1,urlch1l2, etc.). - Abstracts the underlying infection hosts and allows flexible swapping of backend domains or servers with minimal change to the operator’s workflow.

- Internal “short link” infrastructure (often represented in logs as

- Multi-Tier Command-and-Control (C2)

- C2 infrastructure is arranged into multi-level chains (for example

cnc ch 1 l1,l2,l3). - Tier-1 nodes are victim-facing and designed to be burnable; deeper tiers maintain stable, long-term connectivity to customer backends.

- The structure supports:

- Traffic laundering across multiple hops.

- Segmentation of infrastructure per customer / geography.

- Controlled exposure of higher-tier nodes, which are more sensitive.

- C2 infrastructure is arranged into multi-level chains (for example

- Backend Service Layer

Backends are broken out into specialised components, including but not limited to:file-server– provides payloads and may also be used to stage exfiltrated artefacts.api-server– orchestrates infection operations, coordinates sub-systems, issues tasks.config-server– distributes configuration to infection and C2 nodes (domains, chains, exploit profiles, operational parameters).

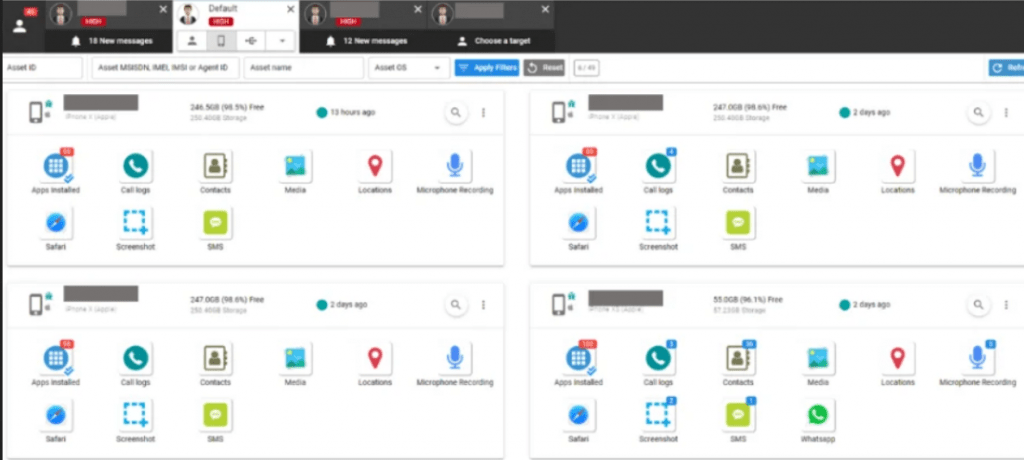

- Predator Dashboard System (PDS)

- Operator-facing web application typically deployed on a backend system reachable via an internal URL (e.g.,

https://pds.[internal.domain]:8884as seen in the leaked video). - Capabilities include:

- Target management (adding/removing “persons of interest”).

- Generation of tailored infection vectors (links, campaigns).

- Real-time visibility into infection attempts and status.

- Browsing of collected data (messages, files, device metadata, recordings).

- Operator-facing web application typically deployed on a backend system reachable via an internal URL (e.g.,

- Centralised Analytics and Logging (Elastic Stack)

- An Elasticsearch cluster aggregates logs from:

- Infection servers (HTTP requests, infection status).

- URL shorteners (link creation and usage).

- C2 nodes (connectivity, command execution, heartbeat).

- Backend services (task dispatch, configuration updates).

- Dashboards used in training sessions display live and historical telemetry at scale, enabling Intellexa staff to review ongoing operations and troubleshoot failures.

- An Elasticsearch cluster aggregates logs from:

The architecture is explicitly multi-tenant in design: the same codebase and system design are reused across government customers, with segmentation primarily implemented at the infrastructure and configuration level (separate C2 chains, domain sets, and log namespaces per customer).

2.2 Functional Capabilities on Compromised Devices

Once a device is successfully exploited and the Predator implant is deployed, the platform provides a full device-takeover capability set on both Android and iOS endpoints. Public research and vendor statements summarise capabilities as:

- Full access to content of end-to-end encrypted applications (e.g., Signal, WhatsApp) by exfiltrating data on the device post-decryption.

- Collection of SMS, call logs, address book, email, photos, files, and application data.

- Continuous or event-driven location tracking.

- Covert activation of microphone and cameras for ambient audio and visual surveillance.

- Device profiling (OS version, patch level, hardware model) to support targeting analytics.

In practice, this equates to persistent, privileged control over the endpoint, with the spyware operating below or beside the application security model.

3. Infection Vectors and Delivery Workflows

The leaked materials confirm two principal delivery models:

- Classic 1-click lures (e.g., via messaging apps).

- Aladdin, an ad-tech based, “almost zero-click” infection channel.

3.1 1-Click Infection via Social Engineering Lures

A documented case in Pakistan provides a canonical instance of Predator’s traditional delivery pattern.

- A human-rights lawyer received a WhatsApp message from an unknown sender posing as a journalist.

- The message contained a URL appearing to belong to a legitimate European news outlet and claimed to link to an article referencing the target.

- Technical analysis by Amnesty’s Security Lab identified the link as a Predator infection URL tied into Intellexa’s backend infrastructure.

Typical execution flow for this vector:

- Target priming

- Adversary constructs a social-engineering narrative (journalist inquiry, legal/official correspondence, political context, etc.).

- Delivery medium is often a trusted application (WhatsApp, SMS, email, social media).

- Link traversal

- Victim taps the link; request is routed to a domain controlled by the threat actor but visually aligned with a benign site (cloned or lookalike content).

- Fingerprinting and gating

- Infection infrastructure fingerprints the device and environment:

- User-agent, OS, browser.

- IP address / geo.

- Possibly additional attributes via JavaScript or HTTP headers.

- Only if victim matches pre-configured criteria does the system proceed to serve the exploit chain.

- Infection infrastructure fingerprints the device and environment:

- Exploit chain delivery

- Browser or in-app webview receives a tailored exploitation sequence targeting the OS and patch status.

- Successful exploitation leads to installation of the Predator implant.

- Self-destruct on failure or anomaly

- The leaked training data and telemetry show cases where infection attempts are aborted because of environmental changes (e.g. network change during exploitation), triggering automatic clean-up and log handling to reduce forensic artefacts.

This 1-click operational model is straightforward but relies heavily on social engineering and the victim taking a visible action (clicking a link).

3.2 Aladdin: Ad-Tech-Driven “Almost Zero-Click” Infections

The most strategically significant element in the Intellexa Leaks is the confirmation and detailing of Aladdin, Intellexa’s malvertising-based infection platform.

3.2.1 Conceptual Design

Aladdin leverages the online advertising ecosystem as a covert, scalable delivery layer:

- Instead of sending a spear-phishing link, the system uses ad placements on websites or inside mobile apps.

- Malicious ad creatives or redirect chains are selectively served to devices associated with specific public IP addresses.

- The infection attempt can occur when a user simply loads a site or app that includes ad inventory; in some configurations, no explicit tap on the ad itself is required (“almost zero-click”).

A critical requirement noted in the leaked material is cooperation from local ISPs:

- ISPs provide mapping between subscriber identities / targets and public IP space.

- These IP ranges are then used to configure highly targeted ad campaigns in ad exchanges or via intermediary demand-side platforms (DSPs).

3.2.2 Operational Flow

An approximate end-to-end workflow, as reconstructed from Intellexa’s own material and infrastructure analysis, is:

- Target nomination

- Customer identifies individuals of interest, along with associated identifiers (phone numbers, addresses, etc.).

- Through ISP collaboration, these identifiers are mapped to current or typical public IPs.

- Ad-tech onboarding

- Intellexa or its controlled front companies register as legitimate advertisers with one or more ad networks / exchanges.

- Entities are typically based in jurisdictions such as Dubai free-trade zones, providing regulatory and transparency advantages. Recorded Future

- Campaign configuration

- Malicious ad campaigns are configured with extremely tight filters:

- IP address ranges corresponding to nominated targets.

- Optional device type/OS/browser profiling when supported by the ad stack.

- The creatives or landing URLs point into Predator’s infection infrastructure.

- Malicious ad campaigns are configured with extremely tight filters:

- Delivery and exploitation

- When the target device loads a page or app that contains suitable ad inventory, the ad network selects the malicious campaign based on IP match.

- The user’s browser or app retrieves the ad or redirect chain, which in turn routes traffic to the infection servers.

- The infection chain proceeds similarly to the 1-click flow (fingerprinting, exploit delivery).

This approach enables:

- Infection without any visible spear-phishing message to the target.

- Repeated attempts controlled via ad-campaign parameters and budget instead of manual link sending.

- Scalability across any surface that loads third-party ads.

Recorded Future’s research notes that corporate entities associated with Intellexa in Dubai are already operationalising this model, and Amnesty confirms the presence of Aladdin in internal Intellexa marketing material.

4. Vendor Visibility into “On-Prem” Government Deployments

One of the most critical aspects of the Intellexa Leaks is evidence that Intellexa staff retain operational visibility and access into customer environments, including installations claimed to be self-hosted on sovereign, on-premises infrastructure.

4.1 TeamViewer Access Pattern

The training videos show Intellexa personnel using TeamViewer to access multiple remote systems, which are described as live customer environments rather than sandboxed demos. Skills training sessions are conducted on these systems. Amnesty International Security Lab

Observable characteristics include:

- A TeamViewer “My Computers” panel listing systems with code names such as

Eagle,Dragon,Phoenix,Flamingo,Fox,Glen,Lion,Loco,Rhino, in addition to shared demo setups. - Intellexa’s own procurement of multiple TeamViewer licences (seven licences around mid-2021) corresponds with the number of active Predator customers observed in infrastructure analyses of that period.

During the demonstration:

- An Intellexa trainer launches a session into a backend system associated with the

Eaglecode name. - The trainer states explicitly that this is a real customer environment, not a test system.

4.2 Visibility into Operational Data

Once inside the remote desktop, the trainer is seen:

- Navigating an Ubuntu desktop environment residing within the customer’s internal network.

- Opening a browser session pointing at an Elasticsearch-backed monitoring dashboard, aggregating logs from:

- Infection servers.

- C2 chains.

- URL shorteners.

- Backend components.

- Scrolling through live and historical Predator events, including:

- Infection URLs and request metadata.

- Target device characteristics (OS version, IP address, browser).

- Infection outcome states and failure modes (for example, dependency on network continuity).

In the same video, a separate browser window shows a login form for the Predator Dashboard System. The field for username is pre-populated (e.g., a user such as cyop), strongly indicating that the same machine is used for direct dashboard access.

This creates a concrete picture of the operational model:

- Intellexa staff can remotely access a customer’s backend, navigate infection logs, observe live operations, and potentially authenticate to the operator UI.

- Customer deployments are, in effect, not fully isolated: they form part of a wider, vendor-visible operational mesh.

This visibility directly contradicts repeated claims from mercenary spyware vendors that they cannot see who customers are targeting or what data is collected, because everything is allegedly processed only within sovereign customer infrastructure.

5. OPSEC Model and Infrastructure Evolution

The Intellexa Leaks include an internal operational security (OPSEC) document that has become a reference for mapping Predator infrastructure. The guidance in that document aligns with patterns identified in multiple public threat-intelligence reports.

5.1 Multi-Tier Infrastructure Strategy

Key characteristics of Predator’s infrastructure design include:

- Multi-tiered C2 architecture:

- Tier-1: victim-facing servers, frequently rotated and domain-fronted.

- Upper tiers (Tier-4, Tier-5): more stable, routed behind CDNs and/or indirect connectivity paths, and often associated with entities or networks tied to Intellexa or its affiliates.

- Use of Cloud and CDN Services:

- Increasing reliance on services such as Cloudflare to obfuscate origin IPs and make direct infrastructure attribution harder.

- Domain Strategy:

- Domains that mimic news outlets, NGOs, and other high-legitimacy entities.

- Rapid rotation and compartmentalisation by region and customer in line with OPSEC recommendations.

The OPSEC documentation reportedly prescribes standard tradecraft practices: minimising persistent identifiers, segmenting infrastructure per customer, and quickly re-provisioning infrastructure after exposure.

5.2 Corporate and Logistics Footprint

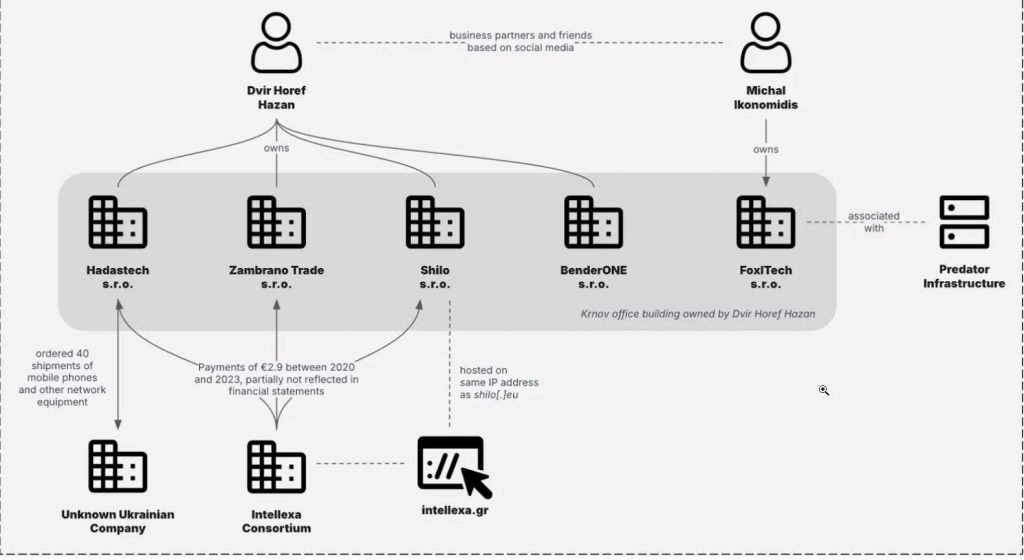

Recorded Future’s “Global Corporate Web” analysis details how Intellexa has progressively reshaped its corporate footprint to maintain operations and facilitate logistics.

Key elements:

- Use of UAE free-trade-zone companies (especially in Dubai and Abu Dhabi) as front entities.

- These entities operate as:

- Ad-tech fronts for Aladdin-style malvertising campaigns.

- Logistics and sales nodes for shipping “data analysis hardware-software complexes” (appliance-like boxes) to client countries such as Botswana, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, and others.

- Ownership restructuring:

- Shares of certain Intellexa-linked Israeli entities have been transferred to Gulf-registered companies, complicating sanction enforcement and due-diligence.

This corporate web is tightly coupled with the technical infrastructure – shipping hardware correlates with the appearance of new Predator infrastructure clusters in those regions.

6. Customer Codenames, Geography, and Targeting

The TeamViewer list and other leaked references use codenames for customer environments, for example: Dragon, Eagle, Falcon, Flamingo, Fox, Glen, Lion, Loco, Phoenix, Rhino.

Publicly documented mappings and inferences include:

- Eagle

- Linked to Kazakhstan, based on the combination of leaked backend context and previous infrastructure and trade-data analysis.

- Phoenix

- Tied in earlier investigations to forces aligned with Khalifa Haftar in eastern Libya, underlining Predator’s use in conflict-affected contexts.

Beyond these codenames, Predator operators and infrastructure have been associated with a diverse set of countries:

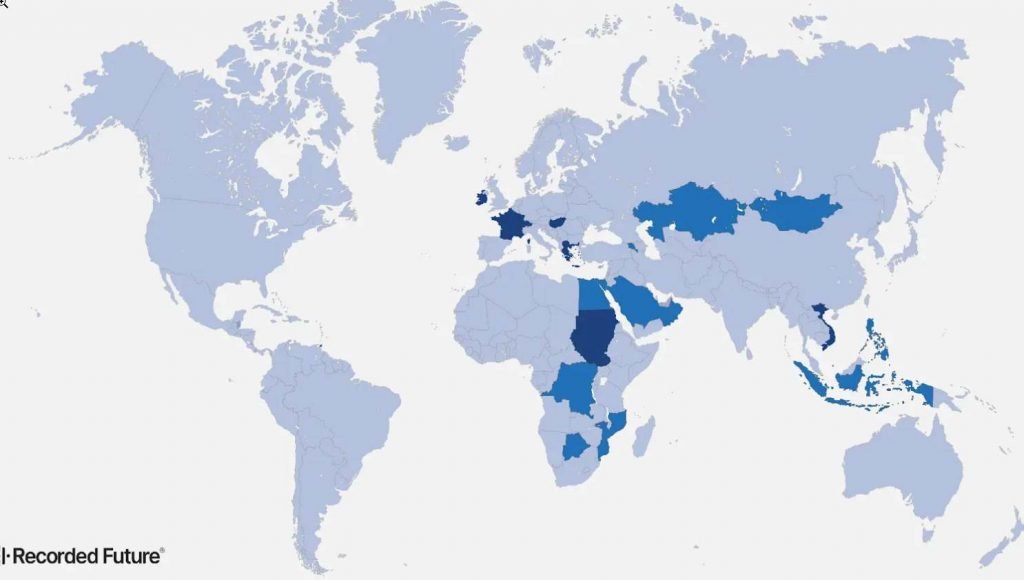

- Previously and/or currently linked customers / operators include entities in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Angola, Mozambique, Iraq, Botswana, Mongolia, Trinidad & Tobago, Philippines, and others, based on infrastructure telemetry and trade data.

- Recent public statements summarising research by Amnesty, Google TAG and others list targets or suspected customers in Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Angola, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Saudi Arabia, Tajikistan, with a broader footprint including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Qatar, Congo, among at least 25 implicated countries.

From the perspective of targeting, cases documented by Amnesty and partner media show recurring patterns:

- Human-rights lawyers and activists (e.g., the Pakistan case).

- Journalists and media professionals.

- Opposition politicians and political insiders.

- Security services, military, judiciary, and business elites in domestic political contexts (for example, Greece’s Predatorgate).

7. Predator in the Greek “Predatorgate” Context

The Greek scandal commonly referred to as Predatorgate is a critical test case for understanding Predator’s deployment within an EU legal environment.

Key elements that intersect with the Intellexa Leaks:

- Confirmed or alleged targets include:

- Investigative journalist Thanasis Koukakis.

- Artemis Seaford, a trust & safety manager at Meta.

- Politicians, high-ranking officials in the military and police, members of the judiciary, and business figures.

- Forensic work by Amnesty and others had already identified Predator artefacts on victim devices in Greece and Egypt prior to the new leaks.

- The Intellexa Leaks add:

- Internal code fragments and identifiers matching those previously recovered from devices.

- Operational evidence (log structures, infection URL patterns, backend naming conventions) that align with Greek and Egyptian cases.

The criminal and parliamentary investigations in Greece now have to reconcile:

- Intellexa’s assertion that it is not operationally involved in targeting decisions.

- The new evidence that vendor employees retained remote access to logs and operational dashboards for at least some customers, with potential visibility into target selections and operation timelines.

8. Technical Observables and Ecosystem Implications

While the Intellexa Leaks are not structured as a defensive playbook, they inherently reveal observables and structural characteristics that frame how Predator fits into the broader security ecosystem.

8.1 Endpoint Perspective

The leaked and corroborated information confirms that, from an endpoint perspective, Predator functions as a full-privilege implant:

- Device compromise yields access equivalent to (or near) system-level control.

- The spyware operates with the ability to bypass application-level security assumptions by collecting data post-decryption, activating sensors directly, and maintaining persistent access.

On consumer mobile platforms, visibility into this layer is constrained; in practice, detection and notification have primarily been driven by:

- OS vendors (Apple, Google) through internal threat-intelligence and telemetry.

- Independent forensic labs and NGOs (Amnesty Security Lab, Citizen Lab, etc.) conducting manual device analysis.

8.2 Network and Infrastructure Perspective

From a network and infrastructure point of view, the Intellexa ecosystem exhibits systematic patterns:

- Hierarchical C2 chains with differentiated tiers, where high-tier nodes are more stable and often linked to entities or networks traceable to Intellexa or corporate affiliates.

- Increasing utilisation of CDNs and cloud edge services to mask origin IPs and central nodes.

- Use of ad-exchange traffic as an infection conduit (Aladdin), blending malicious traffic into ordinary ad delivery flows.

These elements position Predator operations at the intersection of:

- Traditional spyware command infrastructure.

- Commercial web-advertising ecosystems.

- Global cloud fronting and content distribution platforms.

8.3 Governance and Control Model

The governance/ownership model is as significant as the code:

- The combination of vendor-maintained remote access, multi-tenant backend design, and opaque cross-border corporate structures means that Predator operations are neither purely national nor purely private-sector; they are a hybrid.

- Sanctions and regulatory measures target this hybrid space:

- Commerce Entity List and Treasury sanctions on Intellexa Consortium and Cytrox/Intellexa companies.

- European Union scrutiny through, for example, the PEGA committee’s work on mercenary spyware.

The Intellexa Leaks show that, despite legal and political pressure, the technical and corporate machinery underpinning Predator has evolved rather than disappeared—shifting infrastructure, jurisdiction, and delivery vectors while maintaining core capabilities.

From a purely technical vantage point, the Intellexa Leaks reposition Predator as a fully industrialised espionage platform:

- Highly modular, with distinct infection, C2, analytics, and operator layers.

- Natively integrated into the digital advertising and cloud-service ecosystem.

- Architected for cross-customer re-use while preserving vendor-level operational visibility into government deployments.

For the cybersecurity community, this shifts Predator from “one more commercial spyware family” to a reference example of how a modern mercenary surveillance vendor can combine exploit development, cloud-scale infrastructure, ad-tech abuse, and corporate obfuscation into a single, durable operational system.

He is a cyber security and malware researcher. He studied Computer Science and started working as a cyber security analyst in 2006. He is actively working as an cyber security investigator. He also worked for different security companies. His everyday job includes researching about new cyber security incidents. Also he has deep level of knowledge in enterprise security implementation.